Fort Ord closed on September 30, 1994. It was one of the largest U.S. military bases ever shutdown. The closure left behind an area of land the size of San Francisco.

Today the base is home to a university, National Monument and construction is underway on a new joint Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense heath care center. But after 20 years, a lot of work still remains.

Perhaps the best view of Fort Ord comes from high on the hilltops to the east of the former base. From here the relatively small foot print where 36,000 soldiers, federal employees and their families lived and worked now blends in with the surrounding communities that divide up ownership of the former Fort.

More noticeable is the vast amount of open space covered in oaks and maritime chaparral. That’s where Bill Collins drives a large white SUV into a section of that open space called the impact area, roughly 8,000 acres currently closed to the public.

For 77 years, it was a place where soldiers trained on ranges with hand grenades, rockets and riffles. “Then of course the impact area’s center is where the high explosive artillery were also use: 81 millimeter mortars, 105 millimeter howitzer projectiles. And we also have larger items, self-propelled 8 inch artillery explosives that are very dangerous,” says Collins.

Collins has been working on the clean-up for the past twenty years. He’s the Army’s Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Environmental Coordinator.

“It’s a significant effort, I can say that. In the last 20 years, the amount of work the Army has done substantially reduced the hazards with the chemicals and the explosive ordinance,” says Collins.

Collins expects munitions removal will be complete by 2022. It’s a long process that begins with clearing vegetation then a survey team searches for unexploded ordinances. To date they’ve collected more than 50,000.

“Very slow and time consuming, but it’s necessary to be able to remove the explosive hazards on the ground surface, so that the property can be used in the future for habitat conservation,” says Collins.

The impact area is part of the Fort Ord National Monument , a near 15,000 acre federal park, more than half of the former base. The section of the Monument open to the public has a spider web of trails and fire roads for mountain biking, horseback riding and hiking.

“I think when the base closed, the public at large didn’t really know what was out here,” says Michael Salerno, a founding member of the group Keep Fort Ord Wild (KFOW). Now he says he’s out here hiking or biking at least four times a week.

He usually enters the Monument from the west at an unofficial entrance on the corner of 8th and Giggling in Seaside. It’s an intersection where old buildings on the former base meet open space. “You sort of have to be in the know or local because there’s no signage,” says Salerno.

That’s because the Monument is actually a little over a mile away, and to get there, he has to walk through a piece of oak covered land slated for a development called Monterey Downs. It includes plans for housing, retail and a horse racing track.

Base reuse plans assume a certain amount of revenue will come from development; revenue that will, in part, help protect the habitat. But Salerno says KFOW has its sights on stopping this particular project.

“Our mission is pretty simple. It’s to preserve the open space and unique oak forest and support development on the already blighted areas. We call it the existing foot print of the base, where the pavement stopped,” says Salerno.

Where the pavement stopped is where base redevelopment has largely been focused, but blight remains. Just a few steps away from the 8th and Giggling intersection sit vacant buildings with broken windows and boarded up doors. Plans for blighted area came to a halt when the economy tanked. But things are starting to pick up.

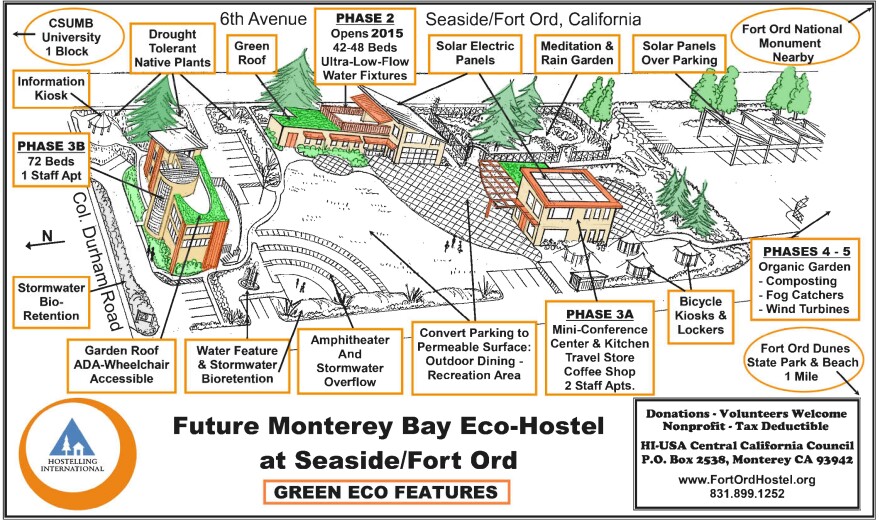

In Seaside, the non-profit Hostelling International is in the process of turning three abandoned buildings into a 120 bed hostel and small conference center called the Monterey Bay Eco Hostel. Phase one of the project is slated to open late 2016 with 48 beds in a building that used to be an infirmary.

This is one of the few projects on Fort Ord that’s still making use of existing structures. Doing so comes with challenges: removing asbestos and lead paint, and making adjustments to be ADA compliant.

“We are finding out that the structural aspect of it to make it earth quake proof is a challenge. So we’re looking at some creative alternatives, something called fiber wrap. It’s a fiber material that has metal in it, and you wrap the building in and it gives the sheer strength. But the question is, is it going to be cost effective,” says Peter Kambas of Hostelling International.

It’s in part why most of the remaining blight will be torn down to make way for new buildings. Just down the road at Cal State Monterey Bay, KAZU’s parent institution, construction of a new business and information technology building is underway in what used to be a parking lot.

Nearby Senior Miranda Allen says campus’s mix of the new and old is part of why she came here. This is where her grandfather did basic training, which helped her earn a scholarship from the Fort Ord Alumni Association. She says she likes the idea that she is getting an education in the same place her grandfather did.

“I felt like we both were doing the same thing. Even though he was going toward an Army career and a police career. I’m also going towards a career, it’s just in a different way,” says Allen.

The next challenge for the redevelopment is keeping this new Fort Ord generation from leaving. “Right now, we’re losing much of our talent because we don’t’ have the ability to offer them the employment opportunities and the jobs,” says Michael Houlemard, Executive Director of the Fort Ord Reuse Authority (FORA).

“So absent those high quality, talented folks staying in this community, we’re losing that sort of brain drain from our region, which is essential to our recovering program,” he continues.

FORA facilitates the former base’s transition to civilian use. It’s hiring an Economic Development Specialist to help attract new businesses that can tap into the area’s growing education community, and outdoor recreation opportunities like those on the very edge of the former fort at Fort Ord Dunes State Park.

This beach was a military firing range and closed to the public. Now, “this is biggest California coastal ocean park in modern history. It’s about 2 ½ miles, 3 miles long. No housing, no development on it, open to the public,” says Congressman Sam Farr as he stands on a bluff overlooking the Monterey Bay.

He’s seen the base transformation from day one, and says while everything has moved slower than expected, he looks to the successes like this park.

“We’re here edge of the largest marine sanctuary in the continental United States. This is where California began. We’re so full of history of different culture, of different meetings of land and water and the environment. It’s nothing but opportunity, and I think that’s the value added that we bring to an otherwise economically depressed area,” says Farr.

There’s no estimate for when Fort Ord’s reuse will be complete, but FORA’s Michael Houlemard expects the former Army base will be 90-percent there by 2030.

“We will have a flourishing National Monument. We will have major new trail networks. We will have a way of connecting the coast to the inland areas. It’ll be a complete and thriving community that we all expected it would be in ’97,” says Houlemard.